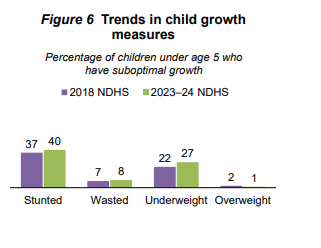

This malnutrition trend was revealed in the National Demographic and Health Survey, conducted by the Ministry of Health, National Population Commission and ICF in October.

The survey reported that children’s nutrition health in Nigeria has suffered considerably over the last six years.

In 2018, 37% of children under five were stunted, 7% wasted, 22% underweight, and 2% overweight. In 2024, these figures have only worsened. Now 40% of children under five are stunted, 8% are wasted, and 27% are underweight.

FIJ understands that the problem goes back even further. By 2015, Nigeria already had the world’s second-highest rate of stunted growth in children under five, with a prevalence of 32%, according to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Poverty and inflation are largely to blame, according to experts. A 2022 World Bank Economic Review paper even drew a straight line between rising food prices and malnutrition.

In June, UNICEF also reported that conflict, inequity, poverty and insecurity have pushed one in three Nigerian children (11 million) into hunger.

ALSO READ: International Day of the Boy-Child: Sexual Abuse Against Boys More Prevalent Than We Know – Opinion

Similarly, Tayo Aduloju, the Chief Executive Officer of the Nigeria Economic Summit Group (NESG), said that 26.5 million Nigerians are at risk of food insecurity due to climate change, inflation and conflict in July.

READ ALSO: 100 Nigerian Children die Hourly from Malnutrition – UNICEF

In Nigeria, the present and the future do not appear so bright. According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the food inflation rate climbed from 30.6% to 37.7% over the last year. The cost of a healthy diet also rose from N1,225 in August to N1,346 in September. Staple food prices have also risen with some doing over 280% on a year-on-year basis.

The impact on families is severe. A recent World Bank report found that rising food prices have driven millions more Nigerians into poverty. In 2024, about 129 million people live below the national poverty line, making up 56% of the population, up from around 40% in 2018.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s National Policy on Food and Nutrition aims to reduce the stunting rate among children under five to 18% by 2025 and cut severe acute malnutrition from 18% to 10%.

With the current figures and conditions, the national policy’s goal looks distant. According to a Wednesday This Day report, Philomena Irene, UNICEF’s Chief Nutritionist, shared that only four out of Nigeria’s 36 states have accessed the fund to fight child malnutrition. This suggests that subnational governments need to step up their game to solve the problem.

—FIJ